Marine snow in the deep sea

In their "NEREIDES" project, Gerhard J. Herndl and his team are investigating unknown aspects of the marine carbon cycle. On two research cruises with the Dutch research vessel Pelagia, the scientists are measuring the flow of organic material from the sunlit surface layers into the deep sea in the Atlantic.

This particle rain, known as "marine snow", is the main source of food for all life in the deep sea.

As part of the project, the researchers are collecting samples of this large pool of organic matter and determining its chemical and biological components. The aim is to determine the origin, source and turnover of this large pool of neutrally buoyant particles as well as the significance of deep-sea marine snow in the Atlantic for the (micro)organisms living there and to investigate its role as a carbon sink under changing climate conditions.

About Gerhard J. Herndl

Gerhard J. Herndl is a marine ecologist and has been investigating biogeochemical cycles and microbial communities and their activities in the deep sea for more than two decades. Before he was appointed Professor of Marine Biology and Biological Oceanography at the University of Vienna in 2008, he was Head of the Department of Biological Oceanography at the Netherlands Marine Research Institute and Professor at the University of Groningen. This is Herndl's second ERC Advanced Grant, the first dating back to 2011, when he also received the FWF's Wittgenstein Award. He has published more than 300 articles in scientific journals and is one of the most cited marine ecologists worldwide.

The path of Homo sapiens through the Levant

Humans evolved in Africa around 250-300,000 years ago and later moved into Eurasia, likely via the Levant. Thomas Higham and his team are investigating when and how often this happened and, in particular, what happened when Homo sapiens first encountered Neanderthals and other kinds of humans, such as the Denisovans. The researchers are focusing on Ksar 'Akil in Lebanon, one of the deepest and most important archaeological sites in the Levant, which is more than 60,000 years old and contains a detailed historical record of when the first modern humans arrived in the region.

In the 'Disperse' project, scientists will reopen the site by removing all fill from previous excavations in the 1930s/40s and 1970s. The latest sediment DNA techniques will be used to determine the presence of different hominins through the archaeological sequence, date the site reliably, analyse its stone tool remains and generate a record of its paleoenvironmental and climatic history. This will allow them to build a reliable record of cultural change through time and understand far more the details of this late period of human evolution. In tandem the team will also work on a number of other sites across Eurasia to explore the timing and dispersal of these earliest humans.

About Thomas Higham

Thomas Higham is Professor of Scientific Archaeology in the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology at the University of Vienna. From 2001 to 2021 he worked at the University of Oxford, latterly as Director of the Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit. He obtained his bachelor's and postgraduate degrees in chemistry at the University of Waikato and the University of Otago in his home country of New Zealand. Higham’s expertise lies in chronometric dating in archaeology and his work focuses on the late evolution of humans, particularly their dispersal from Africa into the rest of the world, and their interaction with other ancient humans. This is the second ERC Advanced Grant of his career.

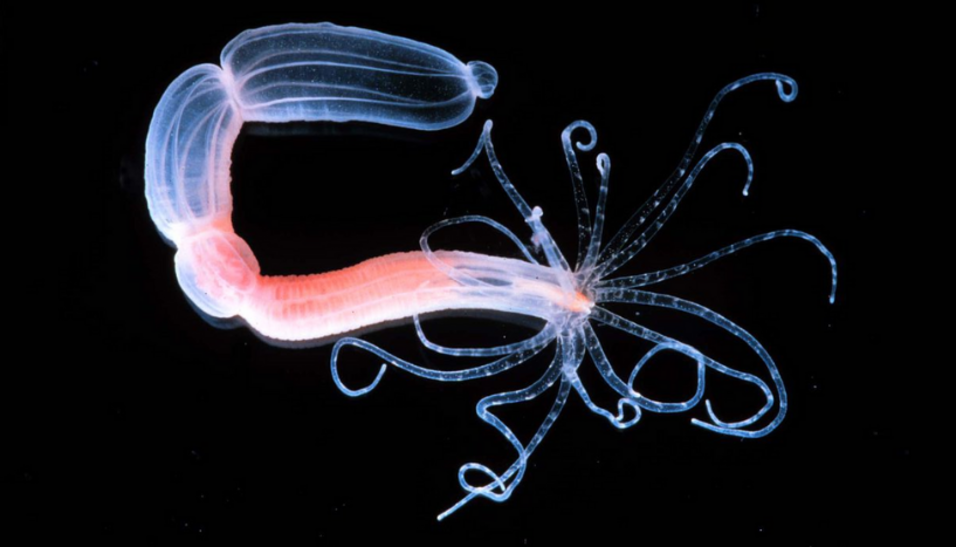

Evolutionary origin of neuro-muscular systems

A characteristic feature of animals is their neuromuscular system, which enables them to perform both slow, non-voluntary movements such as intestinal peristalsis and fast, voluntary movements such as limb movement. This system has contributed significantly to the diversification of body plans, life cycles and cognitive abilities. However, the evolutionary origins of the human nervous and muscular systems and their relationship to neuromuscular systems of simple organisms are still poorly understood.

In his project "EVONeuroMuscle", Ulrich Technau and his team will trace these origins in the early evolution of animals by deciphering and comparing the molecular profiles of muscle cells and nerve cells in Cnidaria (e.g. sea anemones, corals, jellyfish), sponges and comb jellies. Using transgenesis and CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis, the researchers want to elucidate the function of the individual neuromuscular modules in the organism as a whole. In addition, they are developing mathematical and biophysical models to simulate the complexity of the modular systems.

About Ulrich Technau

Ulrich Technau has been Professor for Developmental Biology at the University of Vienna since 2007. He has been studying cnidarians since his master's thesis and investigates how the diversity and complexity of different animal phyla have evolved. Technau studied biology in Würzburg, Mainz, Toulouse and Munich and obtained his PhD in Frankfurt in 1995. After a postdoctoral stay at the University of California Irvine, he habilitated at the TU Darmstadt and moved to the Michael Sars Centre in Bergen, Norway, in 2004. He is an elected corresponding member of the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the German National Academy of Sciences, Leopoldina.

Learn more about: