A study by researchers at the Department of Neuroscience and Developmental Biology, University of Vienna published in Nature Communications has uncovered a surprising difference in how β-catenin functions in sea anemones compared to other animals, challenging assumptions about the evolution of embryonic development.

The role of β-Catenin in early embryo development

During the earliest stages of life, animal embryos must accomplish two critical tasks. First, they need to establish the germ layers – the outer "ectoderm" and the "endomesoderm", which later divides into inner "endoderm" and intermediate "mesoderm". These layers give rise to all embryonic structures – ectoderm forms the skin and the nervous system, endoderm develops into the gut, and mesoderm contributes to muscles, reproductive organs, and more. Second, the embryos need to specify and pattern the body axes, creating a molecular coordinate system allowing correct body parts to develop in correct places. In Bilateria – an incredibly diverse group of animals that includes worms, insects, sea urchins, and humans – β-catenin signaling is crucial for two key developmental processes: defining which cells of the early embryo will form the endomesoderm, and patterning the head-to-tail body axis.

For over two decades scientists believed that β-catenin signaling has the same role in Cnidaria – the evolutionary sister group to Bilateria encompassing corals, sea anemones and jellyfish. However, the peculiar embryology of cnidarians as well as discrepancies between expectations and experimental data suggested that the situation may be more complex.

CRISPR insights show how β-Catenin works differently in Cnidaria and Bilateria

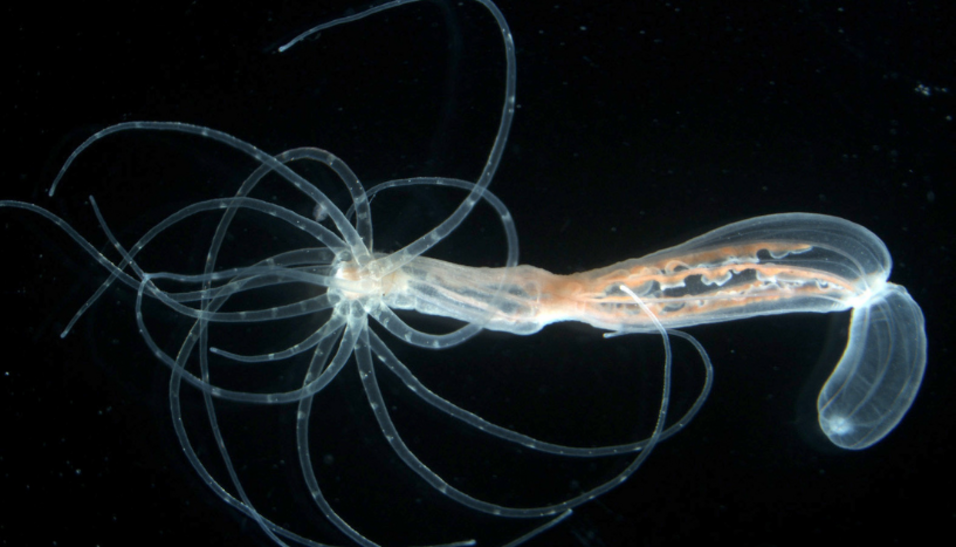

Researchers from the University of Vienna addressed this puzzle using the power of the CRISPR/Cas9 DNA editing technology. Tatiana Lebedeva, a PhD student in the Grigory Genikhovich group at the Department of Neuroscience and Developmental Biology, inserted a DNA sequence coding for green fluorescent protein into the β-catenin gene of the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis. This allowed the researchers to track fluorescent β-catenin during germ layer specification and body axis patterning. Collaborating with the Adameyko group at the Medical University of Vienna, they conducted live imaging of early Nematostella embryos and made a surprising discovery: β-catenin signaling is initially active in all cells except the endomesoderm - precisely the opposite of what occurs in Bilateria.

The study shows that, unlike in Bilateria where β-catenin induces endomesoderm formation, in cnidarians, β-catenin signaling either suppresses endomesoderm specification (as in Nematostella) or has no effect on it (as seen in some other cnidarians). However, subsequent patterning of the main body axis of Nematostella by a gradient of β-catenin signaling intensity works just like in Bilateria.

"Our findings clarify several puzzling discrepancies between theory and experimental data on cnidarian germ layer formation. Clearly, β-catenin-dependent posterior-anterior patterning evolved before the evolutionary split between Cnidaria and Bilateria, and possibly even as early as in the Urmetazoan – the last common ancestor of all animals, as suggested by the work on members of the most "ancient" animal groups - the comb jellies and sponges. However, the role of β-catenin in endomesoderm specification may be a much "newer", Bilateria-specific invention, which tethered the area of endomesoderm specification to the posterior end of the bilaterian embryo – a major evolutionary change!", says Grigory Genikhovich.

Original Publication:

Lebedeva, T., Boström, J., Kremnyov, S. et al. β-catenin-driven endomesoderm specification is a Bilateria-specific novelty. Nat Commun 16, 2476 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57109-w

Contact:

Mag. Dr. Grigory Genikhovich, Privatdoz.

Department of Neuroscience and Developmental Biology

University of Vienna

1030, Wien, Djerassiplatz 1

+43-1-4277-57004